bti225

BTI225 - Week 7

From HTML to the DOM

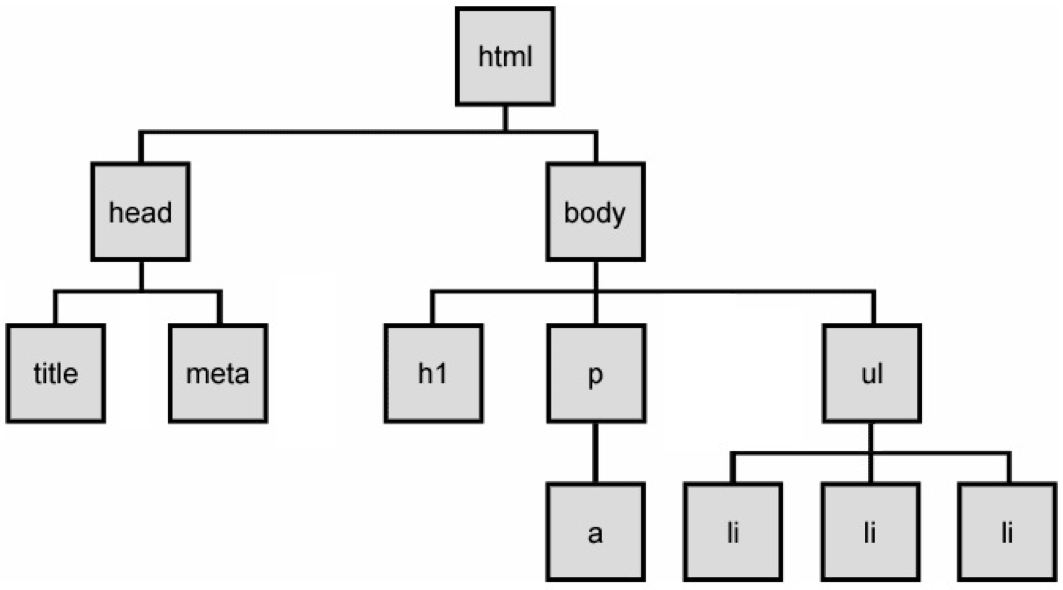

Web pages rely on HTML for their initial structure and content. We write web pages using HTML, and then use web browsers to parse and render that HTML into a living (i.e., modifiable at runtime) tree structure. Consider the following HTML web page:

The DOM Tree is a living version of our HTML.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>This is a Document!</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Welcome!</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph with a <a href="index.html">link</a> in it.</p>

<ul>

<li>first item</li>

<li>second item</li>

<li>third item</li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>

The browser will parse and render this into a tree of nodes, the DOM Tree:

The DOM Tree is made up of DOM Nodes, which represent all aspects of our document,

from elements to attributes and comments. We’ll refer to nodes and elements interchangeably,

because all elements are nodes in the tree. However, there are also other types of nodes,

for example: text nodes (the text in a block element) and attribute nodes (key/value pairs).

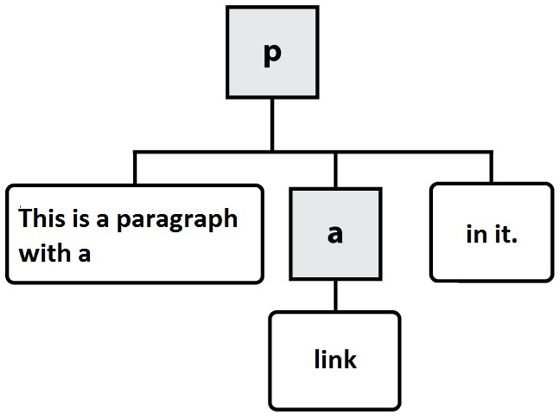

We don’t always show every node in our diagrams. Consider the <p> element from the example

above:

<p>This is a paragraph with a <a href="index.html">link</a> in it.</p>

Here are the nodes that would be created:

In this diagram, the gray, square boxes represent element nodes, while the white, rounded boxes are text nodes.

When we load a web page in a web browser, we see its fully parsed and rendered form. The web browser begins with the initial content we provide in our HTML. We can see the initial source HTML for any page we visit, whether we authored it or not:

Our DOM Tree gets its name because of its shape: a root element connected to child nodes that extend like the branches of a tree. This tree structure is how the browser views our web page, and is why it is so important for us to open and close our HTML tags in order (i.e., our tags define the structure of the tree that the browser will create at runtime).

As web developers we can see and interact with the DOM tree for a page using the browser’s built-in developer tools:

The dev tools allow us to view and work with the parsed DOM elements in a page. We can also use the dev tools to visually select an element in the page, and find its associated DOM element:

NOTE: it’s a good idea to get experience using, and learn about your browser’s dev tools so that you can debug and understand when things go wrong while you are doing web development. There are a number of guides to help you learn, like this one from Google.

Programming the DOM

Web pages are dynamic: they can change in response to user actions, different data, JavaScript code, etc. Where HTML defines the initial structure and content of a page, the DOM is the current or actual content of the page as it exists right now in your browser. And this can mean something quite different from the initial HTML used to load the page.

Consider a web page like GMail (or another email web client). When you visit your Inbox, the messages you see are not the same as when your friend visits hers. The HTML for GMail is the same no matter who loads the page. But it quickly changes in response to the needs of the current user.

So how does one modify a web page after it’s been rendered in the browser? The answer is DOM programming. We’ve been using this “DOM” acronym without defining it, and its high time we did.

The Document Object Model (DOM) is a programming interface (i.e., set of Objects, functions, properties) allowing scripts to interact with, and modify documents (HTML, XML). The DOM is an object-oriented representation of a web page. Client-side web programming is essentially using the DOM via JavaScript to make web pages do things or respond to actions (e.g., user actions).

You may have noticed in our work with JavaScript that there was nothing particularly “webby” about it as a language: we wrote functions, worked with arrays, created objects. Lots of programming languages let you do this. JavaScript can’t do anything with the web on its own. Instead, we need to access and use the Objects, functions, and properties made available to us by the DOM using JavaScript.

As web programmers we use the DOM via JavaScript to accomplish a number of important tasks:

- Finding and getting references to elements in the page

- Creating, adding, and removing elements from the DOM tree

- Inspecting and modifying elements and their content

- Run code in response to events triggered by the user, browser, or other parts of our code

Let’s look at each one in turn.

Finding elements in the DOM with JavaScript

Our entry point to the DOM from JavaScript is via the global variable window.

Every web page runs in an environment created by the browser, and that environment includes

a global variable named window,

which is provided by the browser (i.e., we don’t create it).

There are hundreds of Objects, methods, and properties available to our JavaScript code

via window. One example is window.document,

which is how we access the DOM in our code:

// Access the document object for our web page, which is in the current window

let document = window.document;

NOTE: since properties like

documentare available on the globalwindowobject, it is common to simply writedocumentinstead ofwindow.document, since the global object is implied if no other scope is given.

Our document’s tree of elements are now accessible to us, and we can access a number of well-known elements by name, for example:

// Get the value of the document's <title>

let title = document.title;

// Return a reference to the document's <body> element

let body = document.body;

// Return a list of all <a> elements in the document

let hyperlinks = document.links;

// Return a list of all the <img> elements in the document

let images = document.images;

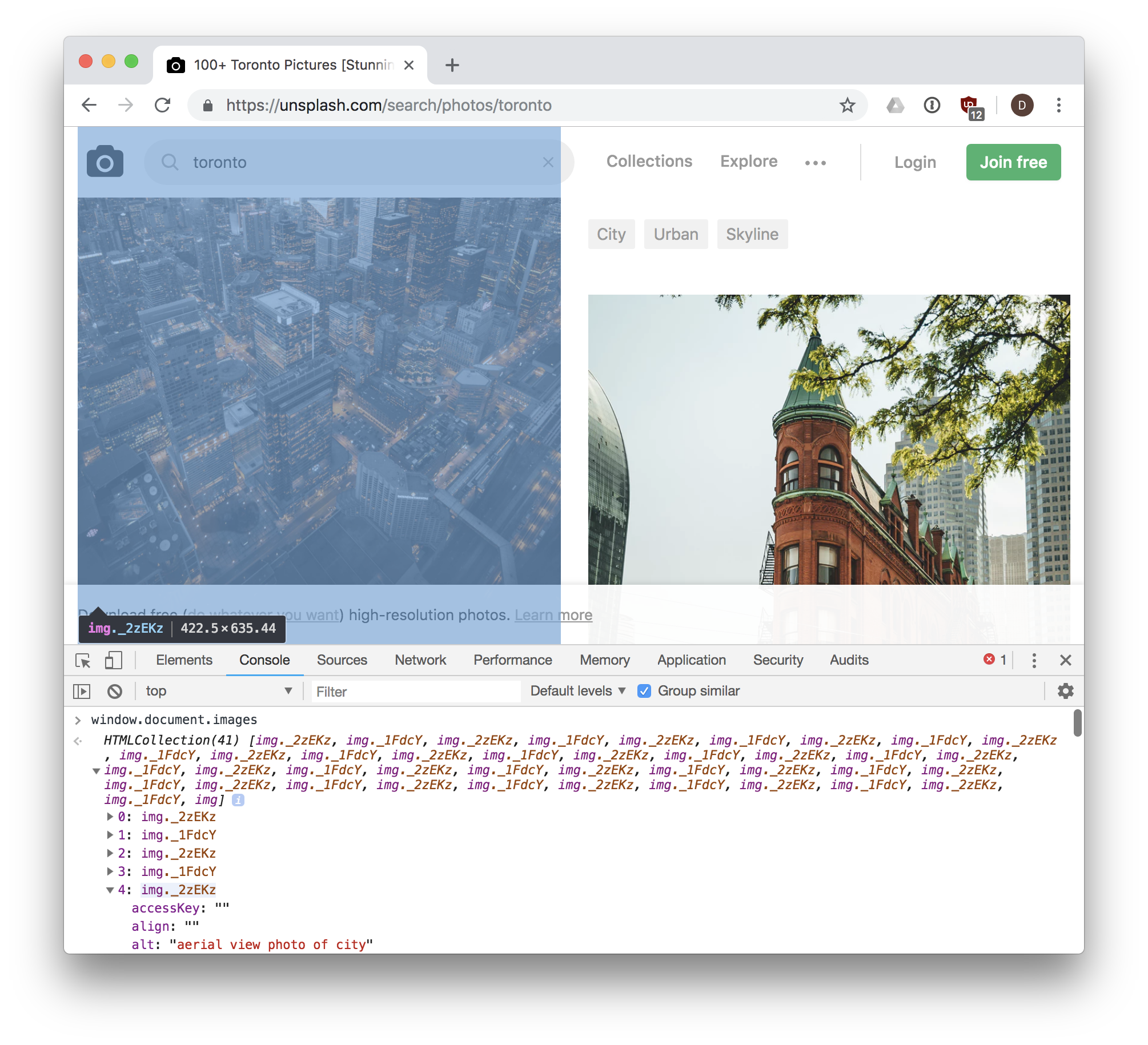

There are lots more. We can easily experiment with these in the dev tools web console,

where we can access our window object. For example, here is the web page

https://unsplash.com/search/photos/toronto with the

web console open, and the result of window.document.images is shown, 41 <img> elements

are returned in a collection:

We can also use a number of methods to search for and get a reference to one or more elements in our document:

document.getElementById(id)- returns an element whoseidattribute/property has the givenidString<div id="menu">...</div> <script> let menuDiv = document.getElementById('menu'); </script>document.querySelector(selectors)- similar todocument.getElementById(id), but also allows querying the DOM using CSS selectors for an element that doesn’t have a unique id:<div id="menu"> <p class="formatted">...</p> </div> <script> // We can specify we want to query by ID using a leading # let menuDiv = document.querySelector('#menu'); // We can specify we want to query by CLASS name using a leading . let para = document.querySelector('.formatted'); </script>document.querySelectorAll(selectors)- similar todocument.querySelector(selector), but returns all elements that match the selectors as aNodeList:<div id="menu"> <p class="formatted">Paragraph 1...</p> <p class="formatted">Paragraph 2...</p> <p class="formatted">Paragraph 3...</p> </div> <script> // Get all <p> elements in the document as a list let pElements = document.querySelectorAll('p'); // Loop through all returned <p> elements in our list pElements.forEach(function(p) { // p is one of the returned <p> elements }); </script>

These four methods will work in any situation where you need to get a reference to

something in document. In fact, you could rely solely on document.querySelector() and

document.querySelectorAll(), which cover the same functionality as a number of other

DOM methods:

// The following two lines of code do exactly the same thing.

// NOTE the use of # to indicate `demo` is an id in the second example.

let elem = document.getElementById('demo');

let elem = document.querySelector('#demo');

Creating elements and Modifying the DOM with JavaScript

In addition to searching through the DOM using JavaScript, we can also make changes to it. The DOM provides a number of methods that allow use to create new content:

document.createElement(name)- creates and returns a new element of the type specified byname.let paragraphElement = document.createElement('p'); let imageElement = document.createElement('img');document.createTextNode(text)- creates a text node (the text within an element vs. the element itself).let textNode = document.createTextNode('This is some text to show in an element');

These methods create the new nodes, but do not place them into the page. To do that, we first need to find the correct position within the existing DOM tree, and then add our new node. We have to be clear where we want the new element to get placed in the DOM.

For example, if we want to place a node at the end of the <body>, we could use .appendChild():

let paragraphElement = document.createElement('p');

document.body.appendChild(paragraphElement);

If we instead wanted to place it within an existing <div id="content">, we’d do this:

let paragraphElement = document.createElement('p');

let contentDiv = document.querySelector('#content');

contentDiv.appendChild(paragraphElement);

Both examples work the same way: given a parent node (document or <div id="content">), add

(append to the end of the list of children) our new element.

We can also use .insertBefore(new, old) to accomplish something similar: add our new node before

the old (existing) node in the DOM:

let paragraphElement = document.createElement('p');

let contentDiv = document.querySelector('#content');

let firstDivParagraph = contentDiv.querySelector('p');

contentDiv.insertBefore(paragraphElement, firstDivParagraph);

Removing a node is similar, and uses removeChild():

// Remove a loading spinner

let loadingSpinner = document.querySelector('#loading-spinner');

// Get a reference to the loading spinner's parent element

let parent = loadingSpinner.parentNode;

parent.removeChild(loadingSpinner);

Examples

- Add a new heading to a document

// Create a new <h2> element let newHeading = document.createElement('h2'); // Add some text to the <h2> element we just created. // Similar to doing <h2>This is a heading</h2>. let textNode = document.createTextNode('This is a heading'); // Add the textNode to the heading's child list newHeading.appendChild(textNode); // Insert our heading into the document, at the end of <body> document.body.appendChild(newHeading); - Create a new paragraph and insert into the document

<div id="demo"></div> <script> // Create a <p> element let pElem = document.createElement('p'); // Use .innerHTML to create text nodes inside our <p>...</p> pElem.innerHTML = 'This is a paragraph.'; // Get a reference to our <div> with id = demo let demoDiv = document.querySelector('#demo'); // Append our <p> element to the <div> demoDiv.appendChild(pElem); </script>

Inspecting, Modifying a DOM element with JavaScript

Once we have a reference to an element in JavaScript, we use a number of properties and methods to work with it.

Element Properties

element.id- theidof the element. For example:<p id="intro"></p>has anidof"intro".element.innerHTML- gets or sets the markup contained within the element, which could be text, but could also include other HTML tags.element.parentNode- gets a reference to the parentnodeof this element in the DOM.element.nextSibling- gets a reference to the sibling element of this element, if any.element.className- gets or sets the value of theclassattribute for the element.

Element Methods

element.querySelector()- same asdocument.querySelector(), but begins searching fromelementvs.documentelement.querySelectorAll()- same asdocument.querySelectorAll(), but begins searching fromelementvs.document-

element.scrollIntoView()- scrolls the page until the element is in view. element.hasAttribute(name)- checks if the attributenameexists on thiselementelement.getAttribute(name)- gets the value of the attributenameon thiselementelement.setAttribute(name, value)- sets thevalueof the attributenameon thiselementelement.removeAttribute(name)- removes the attributenamefrom thiselement

Examples

- Reveal an error message in the page, by removing an element’s

hiddenattribute<!-- The `hidden` attribute means this <div> won't be displayed until it's removed --> <div id="error-message" hidden> <p>There was an error saving the document. Please try again!</p> </div> <script> // Try to save the file, and let error = saveFile(); if(error) { let elem = document.querySelector('#error-message'); elem.removeAttribute('hidden'); } </script> - Insert a user’s profile picture into the page

// Insert the user's picture (e.g., in response to hovering over a username) let profilePic = document.createElement('img'); // Set attributes via getters/setters on the element vs. attributes profilePic.id = 'user-' + username; profilePic.height = 50; profilePic.src = './images/' + username + '-user-profile.jpg'; // Insert the profile pic <img> into the document document.body.appendChild(profilePic); // Make sure the new image is visible, or scroll until it is profilePic.scrollIntoView(); - Add new paragraph elements to a div

// Use .innerHTML as a getter and setter to update some text let elem = document.querySelector('#text'); elem.innerHTML = '<p>This is a paragraph</p>'; elem.innerHTML = elem.innerHTML + '<p>This is another paragraph</p>';

Events

The DOM relies heavily on a concept known as event-driven programming. In event-driven programs, a main loop (aka the event loop), processes events as they occur.

Examples of events include things like user actions (clicking a button, moving the mouse, pressing a key, changing tabs in the browser), or browser/code initiated actions (timers, messages from background processes, reports from sensors).

Instead of writing a program in a strict order, we write functions that should be called in response to various events occurring. Such functions are often referred to as event handlers, because they handle the case of some event happening. If there is no event handler for a given event, when it occurs the browser will simply ignore it. However, if one or more event handlers are registered to listen for this event, the browser will call each event handler’s function in turn.

You can think of events like light switches, and event handlers like light fixtures: flipping a light switch on or off triggers an action in the light fixture, or possibly in multiple light fixtures at once. The lights handle the event of the light switch being flipped.

DOM programming is typically done by writing many functions that execute in response

to events in the browser. We register our event handlers to indicate that we want a particular

action to occur. DOM events have a name we use to refer to them in code.

We can register a DOM event handler for a given event in one of two ways:

element.onevent = function(e) {...};element.addEventListener('event', function(e) {...})andelement.removeEventListener('event', function(e) {...})

In both cases above, we first need an HTML element. Events are emitted to a target element. Elements in the DOM can trigger one or more events, and we must know the name of the event we want to handle.

In the first method above, element.onevent = function(e) {...};, a single event handler is registered

for the event event connected with the target element element. For example, document.body.onclick = function(e) {...};,

indicates we want to register an event handler for the click event on the document.body element (i.e., <body>...</body>).

In the second method above, use addEventListener() to add as many individual, separate event handlers as we need.

Whereas element.onclick = function(e) {...}; binds a single event handler (function) to the click event for element,

using element.addEventListener('click', function(e) {...}); adds a new event handler (function) to any that might already

exist.

Consider the following code:

let body = document.body;

function handleClick(e) {

// Process the click event

}

function handleClick2(e) {

// Another click handler

}

body.onclick = handleClick;

body.onclick = handleClick2;

// There is only 1 click event handler on body: handleClick2 has replaced handleClick.

body.addEventListener('click', handleClick);

body.addEventListener('click', handleClick2);

// There are now multiple, unique click handlers bound to the body's click event.

Because addEventListener() is more versatile than the older onevent properties, you are

encouraged to use it in most cases.

Here’s an example of the first method, where we only need a single event handler. In the following case, a web page has a Save button, and we want to save the user’s work when she clicks it.

<button id='btn-save'>Save</button>

<script>

// Get a reference to our Save <button>

let saveBtn = document.querySelector('#btn-save');

function save() {

// Save the user's work

}

// Register a single event handler on the save button's click event

saveBtn.onclick = function(e) {

// Save the user's work, calling a save() function we wrote elsewhere

save();

};

</script>

Now consider the same code, but with multiple event handlers. In this case we not only want to save the user’s work, but also log the information in our web analytics so we can keep track of how popular this feature is (how many times it gets clicked):

<span id="needs-saving">Document has changes, Remember to Save!</span>

...

<button id='btn-save'>Save</button>

<script>

// Get a reference to our Save <button>

let saveBtn = document.querySelector('#btn-save');

// Register first event handler on the save button's click event

saveBtn.addEventListener('click', function(e) {

// Save the user's work, calling a save() function we wrote elsewhere

save();

// Remove the "needs to be saved" info showing in our UI, since we've saved

document.querySelector('#btn-save').setAttribute('hidden', true);

});

// Register second event handler on the save button's click event

saveBtn.addEventListener('click', function(e) {

// Log some info to the console for debugging.

console.log('[DEBUG] Save clicked');

// Use an analytics Object (defined elsewhere) to update our count for this event

analytics.increment('save');

});

</script>

In this second example, it’s possible for the browser to call more than one function

(event handler) in response to a single event (click). What’s nice about this is that

different parts of our code don’t have to be combined into a single function. Instead,

we can keep things separate (saving logic vs. analytics logic).

A complete example of a page that listens for changes to the network online/offline status, and updates the page accordingly, is available at online.html.

Common Events

There are many types of events we can listen for in the DOM, some of which are very specialized to certain elements or Objects. However, there some common ones we’ll use quite often:

load- fired when a resource has finished loading (e.g., awindow,img)beforeunload- fired just before the window is about to be unloaded (closed)focus- when the element receives focus (cursor input)blur- when the element loses focusclick- when the user single clicks on an elementdblclick- when the user double clicks on an elementcontextmenu- when the right mouse button is clickedkeypress- when a key is pressed on the keyboardchange- when the content of an element changes (e.g., an input element in a form)mouseout- when the user moves the mouse outside the elementmouseover- when the user moves the mouse over top of the elementresize- when the element is resized

All of the events described above can be used in either of the two ways we discussed above.

For example, if we wanted to use the mouseout event on an element:

<div id="map">...</div>

<script>

let map = document.querySelector('map');

// Method 1: register a single event handler via the on* property

map.onmouseout = function(e) {

// do something here in response to the mouseout event on this div.

}

// Method 2: register one of perhaps many event handlers via addEventListener

map.addEventListener('mouseout', function(e) {

// do something here in response to the mouseout event on this div.

});

</script>

The Event Object

In the example code above, you may have noticed that our event handler functions often looked like this:

element.onclick = function(e) {

// e is an instance of the Event object

}

The single e argument is an instance of the Event Object.

The e or event is provided to our event handler function in order to pass information about the event, and to give

us a chance to alter what happens next.

For example, we can get a reference to the element to which the event was dispatched using

e.target. We can also instruct

the browser to prevent the “default” action from happening as a result of this event using

e.preventDefault(), or

stop the event from continuing to bubble up the DOM (i.e., rise up the DOM tree nodes, triggering

other event handlers along the way) using `e.stopPropagation().

Here’s an example showing how to use these:

<button id="btn">Click Me</button>

<script>

document.querySelector('#btn').addEventListener('click', function(e) {

// Prevent this event from doing anything more, we'll handle it all here.

e.preventDefault();

e.stopPropagation();

// Get a reference to the <button> element

let btn = e.target;

// Change the text of the button

btn.innerHTML = "You clicked Me!"

});

</script>

Some events also provide specialized (i.e., derived from Event) event Objects

with extra data on them related to the context of the event. For example, a MouseEvent

gives extra detail whenever a click, mouse move, etc. event occurs:

<div id="position"></div>

<script>

document.body.addEventListener('click', function(e) {

// Get extra info about this mouse event so we know where the pointer was

let x = e.screenX;

let y = e.screenY;

// Display co-ordinates where the mouse was clicked: "Position (300, 342)"

document.querySelector('#position').innerHTML = `Position (${x}, ${y})`

});

</script>

Timers

It’s also possible for us to write an event handler that happens in response to a timing event (delay) vs. a user or browser event. Using these timing event handlers, we scheduling a task (function) to run after a certain period of time has elapsed:

setTimeout(function, delayMS)- schedule a task (function) to be run in the future (delayMSmilliseconds from now). Can be cancelled withclearTimeout(timerID)setInterval(function, delayMS)- schedule a task (function) to be run in the future everydelayMSmilliseconds from now. Function will be called repeatedly. Can be cancelled withclearInterval(timerID)

Here’s an example of using an interval to update a web page with the current date and time every 1 second.

<p hidden>The current date and time is <time id="current-date"></time></p>

<button id="btn-start">Start Timer</button>

<button id="btn-end">End Timer</button>

<script>

let startButton = document.querySelector('#btn-start');

let endButton = document.querySelector('#btn-end');

let timerId;

// When the user clicks Start, start our timer

startButton.onclick = function(e) {

// If the user clicks it more than once, ignore it once it's running

if(timerId) {

return;

}

let currentDate = document.querySelector('#current-date');

currentDate.removeAttribute('hidden');

// Start our timer to update every 1000ms (1s), showing the current date/time.

timerId = setInterval(function() {

let now = new Date();

currentDate.innerHTML = now.toLocaleString();

}, 1000);

};

endButton.onclick = function(e) {

// If the user clicks End when the timer isn't running, ignore it.

if(!timerId) {

return;

}

// Stop the timer

clearInterval(timerId);

timerId = null;

};

</script>

DOM Programming Exercise

In this exercise, we will practice working with HTML, images, URLs, the DOM, events, and JavaScript to create an interactive web page.

- Create a folder called

catson your computer - Create a file inside the

catsfolder namedindex.html - Open a terminal to your

catsfolder (i.e.,cd cats) - In your terminal, start a web server by running the following command:

npx http-server(alternatively, you can use the command:npx lite-server, refer week 5 notes) - Open the

catsfolder in Visual Studio Code - Edit the

index.htmlfile so it contains a basic HTML5 web page, including a<head>,<body>, etc. Try to do it from memory first, then look up what you’ve missed. - Save

index.htmland try loading it in your browser by visiting your local web server athttp://localhost:8080/index.html - In your editor, modify the

bodyof yourindex.htmlfile to contain the text of the poem in cats.txt. Use HTML tags to markup the poem for the web. Your page should have a proper heading for the title, each line should break at the correct position, and the poet’s name should be bold. - Add an image of a cat to the page below the text. You can use https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c1/Six_weeks_old_cat_%28aka%29.jpg.

- Adjust the

widthof your image so it fits nicely on your page. What happens if you adjust thewidthandheight? - Create a new file in your

catsfolder calledscript.js. Add the following line of JavaScript:console.log('cats!'); - Add a

scriptelement to the bottom of yourbody(i.e., right before the closing</body>tag). Set itssrcto a file calledscript.js:<script src="script.js"></script> </body> - Refresh your web page in the browser, and open your browser’s

Dev Tools, andWeb Console. Make sure you can see thecats!message printed in the log. - Try changing

cats!inscript.jsto some other message, save yourscript.jsfile, and refresh your browser. Make sure your console updates with the new message. - Modify

index.htmland update your<img>tag: add an attributeid="cat-picture"and remove thesrc="...":<!-- NOTE: there is no longer a src attribute in our HTML, we'll do it JavaScript below --> <img id="cat-picture"> -

Modify your

script.jsfile to add the following code:window.onload = function() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c1/Six_weeks_old_cat_%28aka%29.jpg'; }; - Save your

script.jsfile and reload your browser. Do you still see a cat? If not, check your web console for any errors. - Modify your

script.jsand change your cat URL used byimg.srcto use https://cataas.com/cat. The cataas.com site provides cat pictures as a service via URL parameters. Savescript.jsand reload your page a few times. Do you see a different cat each time? -

Modify your

script.jsfile to move your image code to a separate function. Make sure it still works the same way when you’re done (save and test in your browser):function loadCatPicture() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; } window.onload = loadCatPicture; -

Rewrite

script.jsto update the picture after 5 seconds:function loadCatPicture() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; } window.onload = function() { loadCatPicture(); // Call the loadCatPicture function again in 5s setTimeout(loadCatPicture, 5 * 1_000 /* 5s = 5000ms */); }; -

Rewrite

script.jsto update the picture every 15 seconds, forever:function loadCatPicture() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; } window.onload = function() { loadCatPicture(); // Call the loadCatPicture function every 15000ms setInterval(loadCatPicture, 15 * 1_000 /* 15s = 15000ms */); }; -

Rewrite

script.jsto update the picture only when the user clicks somewhere in the window:function loadCatPicture() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; } window.onload = function() { loadCatPicture(); // Call the loadCatPicture function when the user clicks in the window window.onclick = loadCatPicture; }; - Modify

index.htmland put a<div>...</div>around all the text of the poem. Give yourdivanid="poem-text"attribute:<div id="poem-text"> <p>Cats sleep anywhere, any table, any chair....</p> ... </div> -

Rewrite

script.jsto load the picture only when the user clicks on the text of the poem:function loadCatPicture() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; } let poemText = document.getElementById('poem-text'); poemText.onclick = loadCatPicture; -

Rewrite

script.jsto also load the picture only when the user presses a key on the keyboard:function loadCatPicture() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; } let poemText = document.getElementById('poem-text'); poemText.onclick = loadCatPicture; window.onkeypress = function(event) { let keyName = event.key; console.log('Key Press event', keyName); loadCatPicture(); }; -

Rewrite

script.jsto also load the picture only when the user presses a key on the keyboard, but only one ofb, m, s, n, p, x:function loadCatPicture() { let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); img.src = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; } let poemText = document.getElementById('poem-text'); poemText.onclick = loadCatPicture; window.onkeypress = function(event) { let keyName = event.key; console.log('Key Press event', keyName); switch(keyName) { case 'b': case 'm': case 's': case 'n': case 'p': case 'x': loadCatPicture(); break; default: console.log('Ignoring key press event'); } }; -

Rewrite

script.jsto also load the picture only when the user presses a key on the keyboard, but only one ofb, m, s, n, p, x, and load the picture with one of the supported cataas filters:function loadCatPicture(filter) { let url = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); // If the function is called with a filter argument, add that to URL if (filter) { console.log('Using cat picture filter', filter); url += `?filter=${filter}` } img.src = url; } let poemText = document.getElementById('poem-text'); poemText.onclick = function() { loadCatPicture(); }; window.onkeypress = function(event) { let keyName = event.key; console.log('Key Press event', keyName); switch(keyName) { case 'b': return loadCatPicture('blur'); case 'm': return loadCatPicture('mono'); case 's': return loadCatPicture('sepia'); case 'n': return loadCatPicture('negative'); case 'p': return loadCatPicture('paint'); case 'x': return loadCatPicture('pixel'); default: console.log('Ignoring key press event'); } }; -

Rewrite

script.jsso that we only load a new cat picture when the old picture is finished loading (don’t send too many requests to the server). Also, add some cache busting:// Demonstrate using a closure, and use an immediately executing function to hide // an `isLoading` variable (i.e., not global), which will keep track of whether // or not an image is being loaded, so we can ignore repeated requests. let loadCatPicture = (function() { let isLoading = false; // This is the function that will be bound to loadCatPicture in the end. return function(filter) { if(isLoading) { console.log('Skipping load, already in progress'); return; } let img = document.getElementById('cat-picture'); function finishedLoading() { isLoading = false; // Remove unneeded event handlers so `img` can be garbage collected. img.onload = null; img.onerror = null; img = null; } img.onload = finishedLoading; img.onerror = finishedLoading; // If the function is called with a filter argument, add that to URL let url = 'https://cataas.com/cat'; // Add something unique (and meaningless) to the query string, so the browser // won't cache this URL, but always load it again url += '?nocache=' + Date.now(); if (filter) { console.log('Using cat picture filter', filter); url += '&filter=' + filter } // Finally, set isLoading to true, and begin loading image isLoading = true; img.src = url; }; })(); let poemText = document.getElementById('poem-text'); poemText.onclick = function() { loadCatPicture(); }; window.onkeypress = function(event) { switch(event.key) { case 'b': return loadCatPicture('blur'); case 'm': return loadCatPicture('mono'); case 's': return loadCatPicture('sepia'); case 'n': return loadCatPicture('negative'); case 'p': return loadCatPicture('paint'); case 'x': return loadCatPicture('pixel'); default: console.log('Ignoring key press event'); break; } };